A federal fisheries vessel sailed north this September, some 12,000 nautical miles (22,200 kilometres) to the Aleutian Islands, the first Canadian patrol of its kind in the North Pacific.

This newly outfitted Canadian Coast Guard vessel, the Sir Wilfrid Laurier, is part of Canada’s effort to ramp up monitoring of the North Pacific to protect salmon that may migrate into international waters near Russia and Alaska.

The patrol vessel sailed from Victoria to Japan, then north in September on a two-month mission near the Aleutian Islands off the coast of Alaska, where a flotilla of industrial vessels gather, their lights appearing as bright as a small city in satellite images.

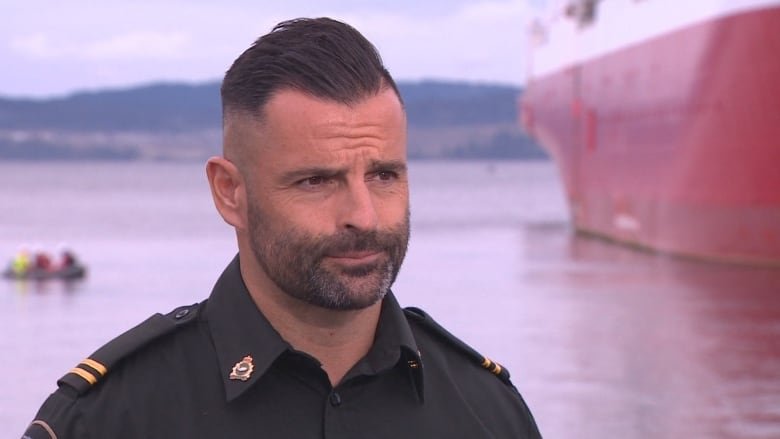

“The radiance of these lights is observed from space,” said senior Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) officer Dustin De Gagne,

The government earmarked $46 million to combat illegal fishing and outfit a special patrol vessel to ply the North Pacific, both to protect fish and keep an eye on remote zones using high seas patrols, flyovers and satellite surveillance.

Last year, the first high seas mission was announced, using a chartered boat. Fishery officers were able to board foreign vessels based on the North Pacific Fisheries Commission’s High Seas Boarding and Inspection Act.

“Only in 2018 did international law change to allow the boarding and a similar inspection regime in the Pacific,” De Gagne said of an inspection regime that had already been happening in the Atlantic under a similar but different international law.

Now, for the first time, Canadian coast guard and fisheries enforcement crews are making patrols in their own dedicated vessel.

The United Nations estimates that between $10 and $ 23 billion US worth of illegal fishing is occurring in international waters each year.

And there are concerns that it is putting some of Canada’s fishing stocks at risk.

De Gagne says that just sailing near the fishing fleets has prompted some to move, and “just being present has a great deterrence effect.”

“There’s approximately 40 million square kilometres of high seas where these vessels can fish, and only a handful of patrol vessels will ever go out there in a year,” he said.

The Sir Wilfrid Laurier has about 50 crew: 20 armed fishery officers, dozens of Canadian Coast Guard crew and two U.S. Coast Guard officers. There are concerns about illegal fishing fleets using drift nets — that can capture 100 tonnes of fish at a time — and about the unintended bycatch of salmon, a species already stressed by a changing climate and higher water temperatures.

Scientists want to know more about how industrial fishing fleets affect salmon returning to Canadian rivers and streams. De Gagne, a senior officer with the Department of Fisheries international enforcement program, sailed to the Aleutian islands with a crew on a chartered ship in 2023.

Now, he’s supporting the crew on a newly outfitted DFO vessel from Victoria, B.C.

The hope is the new patrol will help bolster international co-operation and create better regulations to ensure both fish and the ocean environment are protected.

The crew near Alaska hails ships and then boards them to gather information and data, swabbing vessels to test whether salmon were present.

Dangers at sea

So far this season, the patrol has performed one crew change and resupplied in Yokohama, Japan, returning in heavy weather, that included the remnants of a tropical storm.

By Oct 17, Canadian fishery officers had boarded 15 foreign vessels, finding a dozen infractions, including dozens of shark fins and carcasses, contravening international finning requirements, improperly marked vessels, and failures to report bycatch and comply with vessel monitoring requirements.

They are set to return to port in Victoria by month’s end.

The DFO has spent $19 million on surveillance, including aerial and satellite monitoring and one initial short voyage in a chartered ship in the North Pacific in the past three years, funding for which ends in 2026.

The current patrol is 250 kilometres south of Russia’s exclusive economic zone — the invisible maritime border that extends from a country’s shoreline and denotes its jurisdiction over those waters. The area is often one of wild seas – with swells up to five-metre high — making it dangerous, sometimes impossible, to board a vessel.

But when it’s calm enough, De Gagne says the crew hails ships with flags from various countries, including China, Korea, the Island of Taiwan and Japan. Once on board, they climb sometimes-sketchy ladders into dark holds to perform inspections.

Pacific plays catch-up

De Gagne said, historically, Canadian officials seldom ventured beyond Canada’s 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone — putting them years and several ships behind enforcement efforts in the Atlantic —until last year when they sent a chartered patrol ship to the North Pacific.

Fishery officers in Atlantic Canada have been boarding foreign vessels outside the country’s 200 nautical mile limit for decades under the authority of the 1979 Northwest Atlantic Fishery Organization (NAFO). This came after industrial fishing in the Northwest Atlantic depleted cod stocks.

In the last three years, University of Guelph political ecologist Jennifer Silver says the work being done in Canadian enforcement, which now includes the North Pacific fishery patrols, is positioning Canada as a leader, shining a light on darker aspects of industrial fishing, from over-fishing to exploitative labour practices.

“It’s giving Canada and others an opportunity just to see these parts of the ocean that are very vast and often not visited. So to get a sense for what’s going on out there,” said Silver.

“Fish don’t abide by international boundaries.”

Canada also shares data on “dark” vessels — ships that deactivate their transmitters — in areas that have included the Island of Taiwan, the Philippines and even Ecuador to protect the Galapagos islands, according to DFO.

“Countries are turning their eyes outwards to their own exclusive economic zones and beyond to try and understand what’s going on and how to better keep an eye on them. It has to do with sovereignty,” said Silver.

In Juneau, Alaska, Cmdr. Joseph Anthony, the deputy chief of maritime law enforcement for the U.S. Coast Guard, says this data sharing has been “game-changing.”

He describes the new North Pacific patrol as “groundbreaking,” adding that it keeps eyes on remote zones of the high seas close to Russia. At certain times of the year, he says, Canada’s new ship is “our eyes on the water,” keeping watch on fishing, ship movements authorized by Russia and any trouble on the horizon.