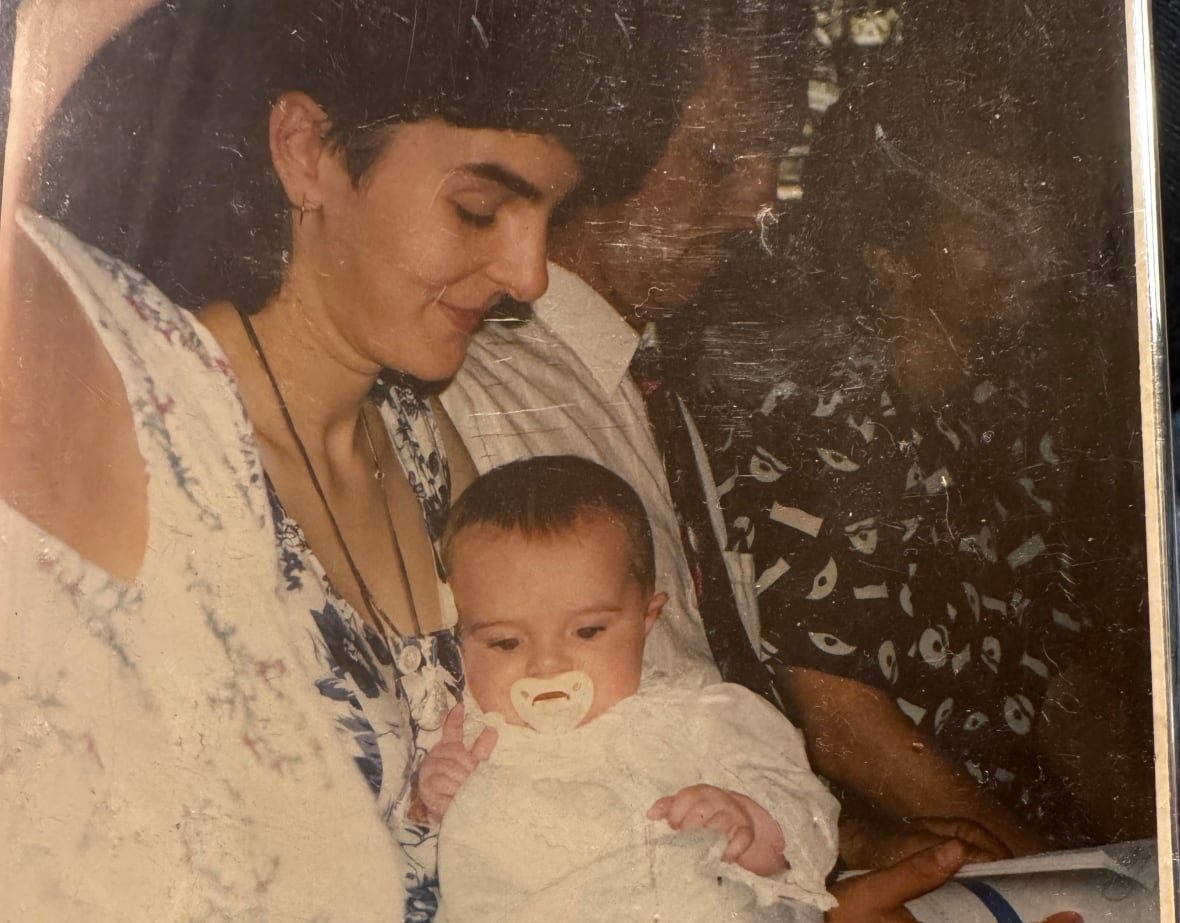

Jennifer Craft says she did everything right when she received an Ontario child-care bursary in 1996 as a single mother.

The money was to help pay for daycare for her two-and-a-half-year old daughter while she studied at Fleming College in Peterborough, Ont., and that’s how it was used, she says.

“It helped subsidize some of that cost so that I could go to nursing school and provide a better life for ourselves,” said Craft.

But Craft was recently contacted by a collection agency seeking that money because she allegedly failed to provide receipts to demonstrate the $1,245 was spent properly.

First came the automated calls in late 2023 and early 2024 from the agency addressing Craft by her maiden name, which she changed after getting married in 2000.

- Got a story you want investigated? Contact the Go Public team

“It’s hard to prove now, 30 years later, that I did the appropriate things,” she told Go Public. “I don’t even keep tax documents longer than eight years. How am I going to find 30-year-old child-care bursary receipts?”

“Even in court, you’re innocent until proven guilty. I’m being proved guilty until proven innocent.”

A woman who received an Ontario child-care bursary nearly 30 years ago while attending nursing school tells CBC Go Public about being asked to show proof of how she used the money or pay it back.

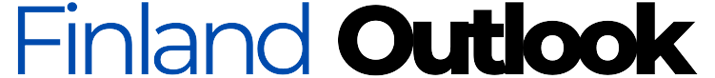

The collection agency forwarded Craft two letters in September 2024. The first, which the college had sent her in 1996, asked for her child-care receipts. The other was from Ontario’s Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities, supposedly sent in 2000, requesting full repayment of the bursary, which was now considered an “overpayment” because previous attempts to contact her about providing receipts were unsuccessful.

But Craft says she submitted those receipts and even confirmed this, over the phone, with the college back in ’96. She says she never received the second letter.

“It wasn’t like I lived in Timbuktu. They could have found me [in] the last 30 years,” she said.

Craft, who now lives in Yellowknife, says the money allowed her to become a nurse and to contribute to her community, particularly during the pandemic when she was a frontline worker — as director of care at three different long-term facilities in Toronto, Picton and Belleville.

Throughout her career, Craft has also worked as a nurse in B.C., N.W.T. and Nunavut. She moved to Yellowknife in late 2023.

“I was a productive member of society. I paid my taxes. The child in question is now 32 and has two kids of her own. So it even seems a little silly that you’re suing a grandma for a child-care bursary.”

No time limit

The collection agency, Financial Debt Recovery, says it cannot speak to individual repayment cases.

The ministry also says it cannot address Craft’s case, but in an emailed statement said overpayments must be repaid.

“There is no limitation period applicable to the collection of debts owed to the Crown,” said spokesperson Dayna Smockum.

And yet, one Toronto-based insolvency trustee says it’s unreasonable to expect people to provide proof of payment after so much time has passed.

“There’s the law and there’s common sense,” said Doug Hoyes.

“I think practically speaking, [officials] have to say, ‘Look, this is too long. There’s no way the person can prove one way or the other what happened.'”

“If this had been a few months after the fact, the person would have been able to say, ‘Well sure, I can contact the daycare centre. Here’s the receipts, I’ve got them. Here’s my bank statement,'” he said.

Normally, under Ontario law, creditors have two years to pursue a debt and, if necessary, file a civil claim. If they win they can garnish wages, put a lien on a house or freeze bank accounts, says Hoyes.

But there are exceptions in Ontario for certain debts owed to the Crown, says Karen Fellowes, an insolvency lawyer in Calgary. She says provinces set time limits on debt collection for good reason.

“The idea is that people shouldn’t have to live with this sort of cloud of potential debt hovering over them for an indefinite period of time.”

Fellowes also says these types of cases can be challenging to prove because with time records can disappear and people’s memories can fade.

After Go Public contacted the ministry it said students “have the option to dispute any bursary repayment case and provide supporting documentation. In the absence of documentation, the ministry will accept a sworn affidavit.”

It’s unclear if this was always an option. Craft says it was not, based on what she was told.

Craft said obtaining that will require taking time off work and spending money on a lawyer but she’s glad she doesn’t have to repay the $1,245.

“For as much work as the government has put in to get it back, seems a little ridiculous,” she said.

Craft says she worries about her former classmates who also relied on financial aid to complete their studies.

“There [were] a lot of nurses that were in the same boat that I was, that were single parents or low income people that were trying to better their lives,” she said.

Submit your story ideas

Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC-TV, radio and the web.

We tell your stories, shed light on wrongdoing and hold the powers that be accountable.

If you have a story in the public interest, or if you’re an insider with information, contact gopublic@cbc.ca with your name, contact information and a brief summary. All emails are confidential until you decide to Go Public.